Note:

- Other Languages :

- Download PDF :

- The Unique Architecture of Ancient Baloch Martyrs’ Graves :

- Flowers as a Symbol of Martyrs :

- Source of the Symbol of Martyrs :

- Baloch Stone Carvers Who Gave Voice to Lifeless Stones :

- The Baloch Pyramids (Tuta Chaukundi) :

- The Connection of This Symbol with Other Cultures :

- Explanation of the Baloch Martyrs’ Symbol :

This essay has been written by Qazi Dad Mohammad Rehan, Secretary of Information and Culture of the Baloch National Movement (BNM). It explores the historical, philosophical, scientific, cultural, and artistic dimensions of the symbol. The document has been preserved as part of the organization’s official record to ensure that the Symbol of Baloch Martyrs is always understood in its true and proper context.

The symbol was formally adopted by the Baloch Martyrs Memorial Council ( Šahmīrānī Tāk ) of the Baloch National Movement (BNM) on October 30, 2025, as the official emblem representing the Baloch martyrs.

Before its selection, extensive consultations were held both within and outside the party to shape it into a consensual and representative emblem.

This paper encompasses the discussions and questions that arose during that process.

Other Languages :

Urdu : https://martyrs.thebnm.org/?p=8664

Farsi : https://martyrs.thebnm.org/?p=8661

Download PDF :

The Unique Architecture of Ancient Baloch Martyrs’ Graves :

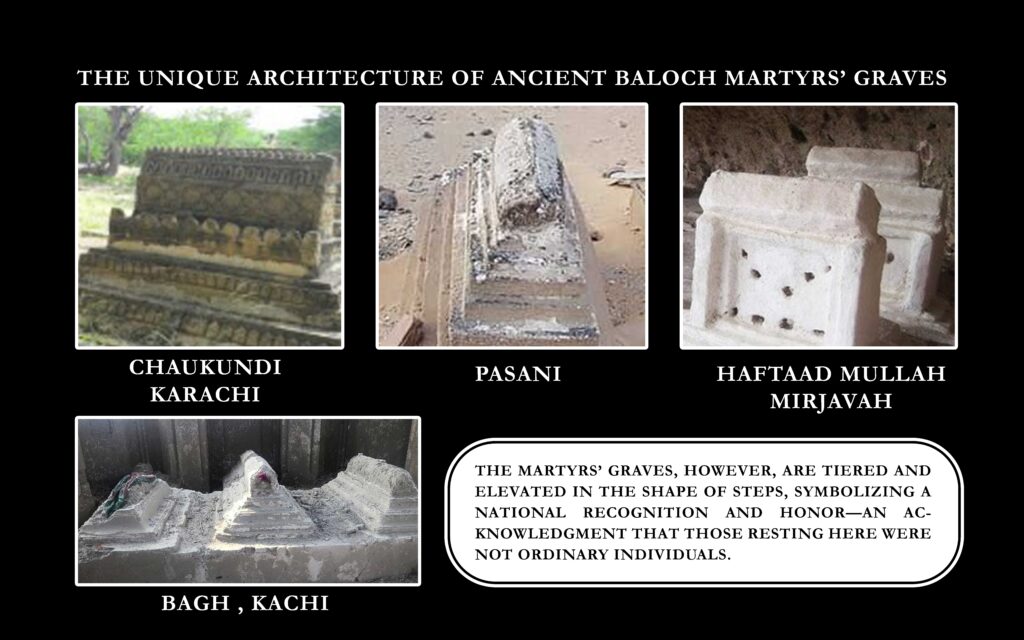

Across the vast Baloch homeland — in regions such as Gwadar, Kachi, Mirjawa, and Tuta Chaukundi (Karachi) — there exist numerous graves of Baloch warriors (Sarmachars) who sacrificed their lives defending their land against foreign invaders.

It has been observed that the graves of these martyrs are distinctly different from ordinary graves. In several burial sites, people from the same period are interred nearby, yet their graves follow conventional forms. The martyrs’ graves, however, are tiered and elevated in the shape of steps, symbolizing a national recognition and honor—an acknowledgment that those resting here were not ordinary individuals.

In many parts of Balochistan, a flower motif is carved on the graves of martyrs — a traditional symbol of honor, reverence, and remembrance. Remarkably, the design and architectural patterns of these graves remain strikingly consistent across the wider Baloch homeland. The flower is often inscribed within a circular form, not merely for ornamentation, but as a reflection of ancient mystical and philosophical conceptions of life.

The repetition of circles and symbols in specific patterns represents notions of balance, harmony, and cosmic order. In the language of symbols, such motifs express the belief that the person who sacrificed their life for their land, people, and identity has not truly died but has become eternal — destined to return in another form. This mystical idea reflects the Sufi belief that life, though it appears to end, continues in other forms or re-emerges in new manifestations. It also suggests that the artisans who engraved these symbols were not merely skilled builders but were also versed in spiritual and metaphysical knowledge.

In Balochistan, it was a long-standing custom that epitaphs were written by educated individuals. Writing the epitaphs of one’s elders was considered an honor and a blessing. In the cemetery of Mand, where the tombs of Shaheed Waja Ghulam Mohammad Baloch and Mulla Fazul stand, several old graves bear inscriptions penned by Mulla Qasum, brother of Mulla Fazul and a renowned poet, whose name appears as the scribe on those stones.

Similarly, the epitaph on my great-grandfather’s grave was inscribed by my grandfather, Qazi Dad Mohammad Rehan, who also signed it with his name as the writer. In the old cemetery of Gwadar, the mausoleum of Amir Kambar bears a Persian inscription stating:

“This mausoleum was constructed by Hōt Mīrān for Mullā Amīr Kambar in the month of Shaʿbān, on Monday, in the year 1140 AH (Hijri lunar calendar), at the end of the kingdom of Shay Bilāl.”

( Persian inscription: Banā kard īn maqām rā Hūt Mīrān barā-yi Mullā Amīr Kanbar be-tārīḵ-e šahr-e Šaʿbān, rūz-e dušanba, sanah-ye yek-hazār o yak-sad o chehel, dar itmām-e bādšāhī-ye Šay Bilāl.)

This demonstrates that building and decorating the tombs of revered ancestors and respected personalities was regarded as an honorable and sacred act in Baloch society — a tradition that was celebrated with pride.

It is not unlikely that this tradition evolved from the Chaukhandi-style tombs, where learned stone carvers once practiced their craft. In some remote areas, even solitary graves display similar engravings, suggesting that stone carving was once a widespread art form.

Although these graves were constructed after the advent of Islam, during a period when the Baloch gradually transitioned from Sanatan Dharma (Hinduism), Zoroastrianism, and Buddhism to Islam, no community in the region can claim a deeper historical attachment to Islamic tradition than the Baloch. Historically, the Baloch were among the earliest nations to embrace Islam, allying with the Arab forces under Sardar Shah Sawar during the reign of Caliph Umar against the Sassanian Empire, following internal disputes within Persia.

However, the artistic motifs on these graves do not originate from Islamic ideology or aesthetics. In Arab culture, both before and after Islam, graves were typically plain and unadorned. Islamic teachings emphasized simplicity to the extent that even epitaphs were discouraged. Arab graves were usually shallow pits, sometimes marked only with simple stones or palm branches.

Therefore, it can be stated with confidence that the architectural style and engravings found on graves across our region are rooted in indigenous cultural traditions, not in so-called Islamic art. Indeed, despite Islamic prohibitions, some Baloch graves depict animal forms, such as horses and horsemen on the tombs of warriors — though overall, the artisans exercised notable restraint in such depictions.

Among the tiered Baloch graves, those in the Haftad Mulla cemetery in the village of Rups (Mirjawa) are particularly remarkable. Estimated to be around a thousand years old, they are sometimes mischaracterized as examples of “Islamic architecture.” Local tradition holds that the martyrs buried there fell fighting against Mughal invaders.

As often happens with Baloch history, efforts have been made to distort or obscure the true identity of those interred in these historic graves. While their exact biographies and individual names remain unknown, the geographical spread and stylistic consistency of such graves — stretching from western to eastern Balochistan — strongly indicate that these too are Baloch graves.

Not all tombs in Haftad Mulla are identical in form, which further supports the idea that the more elaborate structures were built in honor of exceptional individuals. Their architectural distinction serves as a tribute, a recognition of their valor and spiritual greatness.

Although these graves bear no inscriptions, their tiered, step-like structure and conical upper form unmistakably correspond to the distinctive architectural style identified with the graves of Baloch martyrs throughout the region.

Flowers as a Symbol of Martyrs :

Around the world, flowers are a universal symbol of honoring martyrs. In every region, locally grown flowers are used as a representation of respect or remembrance for those who have sacrificed their lives. For instance:

- In Canada, North America, the UK, and European countries, the red poppy is widely used, especially in ceremonies commemorating those who died in World War II.

- In Germany and Japan, the white chrysanthemum serves as a symbol of remembrance.

- In Iran, the tulip is used.

- In Turkey, India, and other countries, roses and various other flowers are employed.

- In some cultures, even the cabbage flower has been used symbolically to honor the fallen.

In Balochistan, the flower most commonly found is the “Jawr” (Olander), known in Persian as Khrazharah. Worldwide, this flower is renowned for its beauty, resilience, and perennial nature. After the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, the first plants to survive radiation included this flower, which came to symbolize hope. It has also been used to restore greenery in lands devastated by storms and floods.

However, in the specific cultural context of Balochistan, there is no traditional practice of decorating or using this flower for ceremonial purposes In modern times, the Jawr flower can be seen in gardens, courtyards, and along roads in many climates worldwide, often cultivated in nurseries and pots.

Other local Baloch flowers include:

- Nazbu (Basil /Rehan) and Jasmine.

- Tulips, which grow in colder regions, though they arenot native to most areas of Balochistan.

A common misconception is that tulips are the national flower of Balochistan — this is not accurate, as many local people are unfamiliar with it. Similarly, every region has its own wildflowers, which bloom seasonally but have largely remained outside mainstream urban life. Among local flowers, only Nazbu and Jasmine are traditionally grown in courtyards, while roses are mainly known in poetic references.

In coastal regions, Nazbu flowers are used for funerals, graves, and Fatiha recitations. Theirsmall flowers are secondary to the aromatic leaves, which are also used in salads.

In Baloch poetry, flowers such as:

- Rose

- Jasmine

- Pomegranate (Gul Anar / Anar Pul)

- Jawr

…are frequently used to express beauty and romantic sentiments.

Despite its charm, the Jawr plant’s leaves are poisonous — it is believed that if a camel eats them, it will die. This has led to proverbial uses expressing curses or negative connotations. Yet, poets could not ignore the aesthetic appeal of the Jawr flower, celebrating its beauty despite its bitter properties.

The Baloch Martyrs Memorial Council of the BNM has proposed the Jawr flower as the symbol of martyrs, based on its unique qualities:

- It -thrives under harsh conditions.

- It symbolizes resilience and life.

- It is found across every region of Balochistan.

Historically, the people of Balochistan have not shown exemplary interest in cultivating flowers, which is understandable given the demands of pastoralism and agriculture. Yet, many indigenous plants and herbs remain untended, waiting to be grown in courtyards and nurseries. Many local flowers possess unique beauty capable of drawing attention, though urban migration and changes in livelihood have caused younger generations to become unfamiliar with them, even though earlier generations knew them well.

Despite this historical indifference, the Baloch have still chosen the flower as a symbolic marker on graves, a universal emblem of respect for the dead, enduring connection, and the cycle of life and rebirth.

Source of the Symbol of Martyrs :

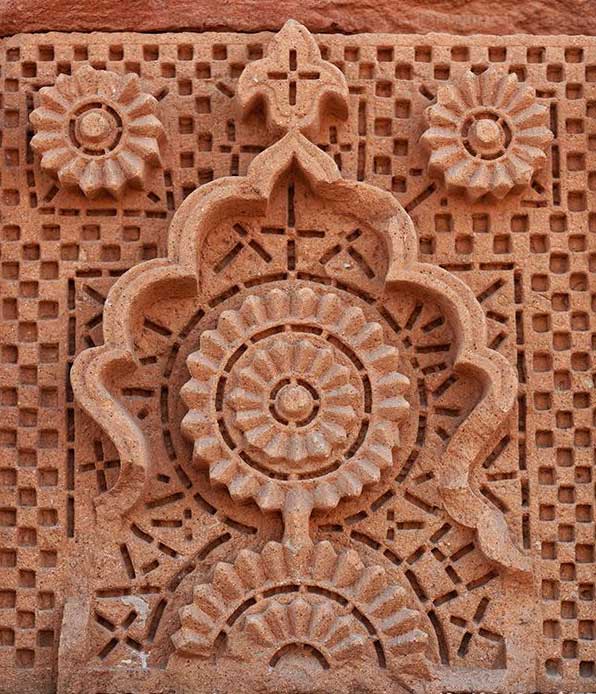

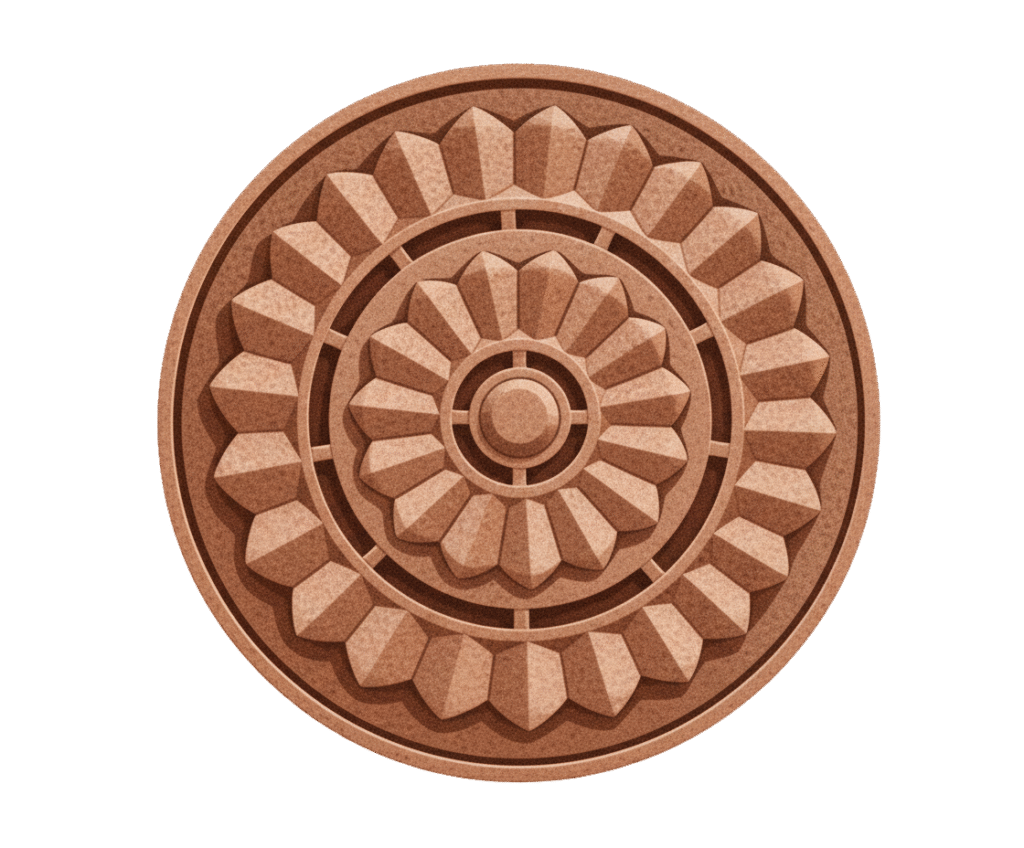

The symbol we have chosen is derived from the engraving on a grave in the famous Tuta Chaukundi cemetery, where many brave Baloch warriors who fought against the Portuguese, Mughals, and other coastal invaders are buried. Generations of Baloch have sacrificed their lives to defend their homeland. This continuity of sacrifice is reflected in the fact that at one time, the cemeteries of Gwadar and other towns were even larger than the settlements themselves.

This symbol is not merely a computerized vector design, like those commonly used today for monograms. It is a carefully restored visual representation based on the engraving of a Chaukundi grave. Several days were spent transforming the stone carving into a modern vector symbol while preserving its original meaning and integrity. Dozens of versions were created and tested in various formats to ensure that it remains clear and recognizable when printed on paper, posters, or even as a badge.

This historical and national symbol reminds us of the heroic deeds of our ancestors, who defended their homeland through martyrdom. During many periods of subjugation, numerous local symbols were erased from collective memory, while foreign occupiers and their historians deliberately avoided acknowledging Baloch heritage as inherently Baloch. Baloch forts, cemeteries, and monuments were attributed to outsiders, and our collective memory was easily obliterated. By assigning foreign names to these places, they denied the reality that the true heirs of this land are the Baloch, whose history is embedded in every particle of this soil.

Psychological subjugation—the alienation from one’s land and traditions—is often disguised as voluntary compliance, but it is an instrument that can erase entire nations. We Baloch know this well. As our proverb says: Rāj pe mīrag gār nah bīt, rāj pe karg gār bīt. (A nation does not perish by death; it perishes by submission.)

Baloch Stone Carvers Who Gave Voice to Lifeless Stones :

The art of stone engraving, including intricate geometric and floral carvings, originated within Baloch society rather than being influenced by external cultures. Even today, Baloch women preserve this remarkable artistic heritage through embroidery , which mirrors the patterns and motifs of traditional stone carving.

The geography of Balochistan has always been harsh, limiting the growth of large and permanent settlements. The Baloch, being primarily herders, relied on vast grazing lands to sustain their large herds and practiced seasonal migration within their own territory. The stories of these seasonal journeys have been immortalized in Baloch poetry.

During the rule of the Bingu family (Bingū Dūdmān) (or Kalmat dynasty), the Baloch became politically and diplomatically strong , securing a prominent position in mediating with new settlers. Their center of authority in Makءran was Kech. Both the Ottoman Empire and Persian monarchies recognized them as a reliable and powerful ally. Even the Afghans regarded the Baloch not merely as neighbor but as a protector friend.

Regional Persian poets praised the Baloch in their role as frontier guardians, honoring their bravery, integrity, and loyalty. For instance, the Persian poet Adib al-Mulk Farahani wrote: Ṣulḥ kardam be Marzabān-e Balūch. Ḥukmdār-e Herāt rā čaknam.

( I have made peace with the Baloch border guardian; now what shall I do with the ruler of Herat? )

This illustrates the high esteem in which the Baloch were held as protectors of the region’s borders, reflecting their strategic and honorable role in the geopolitics of the time.

The Baloch Pyramids (Tuta Chaukundi) :

The Chaukundi cemetery is located along the highway east of Karachi, near the Malir River, approximately thirty kilometers from the city center. The graves at Chaukundi date from the 14th to the 18th centuries, a period when the Kalmat tribe established its dominance over the Baloch coast.

The term Chaukundi comes from the Balochi language: “Chau” meaning four and “Kund” meaning corner, referring to rectangular or square shapes with four corners. Stones for construction were carved in specific geometric proportions, with uniform thickness and weight, and were known as Chaukundi stones. These stones were expensive, and engraving them with decorative motifs required great skill, making this style of grave exclusive to notable individuals.

Initially, Chaukundi graves and floral motifs were reserved for those martyred in battle. Over time, however, they became symbols of wealth, prestige, and social standing, and eventually, each tribe began constructing such graves for its dead to display status. Gradually, having a Chaukundi-style grave came to signify honor, respect, and rank. At Chaukundi, the tomb of Jam Murid bin Haji bears the inscription “Ṣāḥib-i Chaukundī”, indicating either the person buried within or the owner of the Chaukundi grave.

This architectural style is purely Baloch and can be found along the coastal areas of Balochistan. Due to neglect by rulers, much of this heritage has been destroyed or is near extinction. In Gwadar, no columnists or researchers have studied these graves, and although the Pasni Chaukundi graves have attracted media attention, the Department of Archaeology has largely ignored them. This is not mere negligence but intentional oversight, aimed at erasing the glorious history of Baloch resistance.

The stone carvers of Makuran were highly renowned and even contributed to the construction of the Tāj Maḥil in Agra. Today, many Baloch families in Agra remain connected to architecture and stone carving. Baloch artisans were so skilled that they did not need to hire outside craftsmen to construct their graves. Historical accounts show that the Baloch deeply honored their capable members upon death, especially those who sacrificed their lives defending Baloch codes of conduct and traditions. Just as they fiercely defended the borders of their homeland, they safeguarded their cultural boundaries, often fighting to the death against violations. Some legends even claim that certain graves were built using camel milk instead of water, reflecting the extraordinary respect for the deceased.

When the Kalmat tribe extended its control along the coast to the Indus River and established settlements in Malir, they brought this architectural style from Balochistan to Sindh. The Chaukundi cemetery in Karachi, known today as Tuta Chaukundi, was established by the Kalmat tribe. Later, other Baloch tribes adopted this style for their dead. When governance passed from the Kalmat tribe to other Baloch groups, this architectural heritage was preserved. Most of these graves were constructed during times of war. Jam Murid himself resisted the Mughals during Emperor Shah Jahan’s reign, preventing them from establishing dominance over Baloch settlements.

Undoubtedly, the remaining Chaukundi graves stand as some of the most remarkable examples of Baloch architecture. They represent the zenith of Baloch stone carving, which is why I refer to these graves as the “Pyramids of the Baloch.” Here, one can still witness the grandeur, bravery, resistance, and governance of the Baloch carved into lifeless stone.

The Connection of This Symbol with Other Cultures :

It is an undeniable truth that the land we inhabit and our sense of national identity are deeply connected to other peoples through language, culture, clothing, and shared customs.

The Baloch nation holds a unique position in this regard: on one hand, it has strong ties with the people of the Indian subcontinent, and on the other, it is historically and culturally linked to the Middle East and the Arab world. This should not be a source of embarrassment; rather, being a custodian of shared heritage is a matter of pride.

If we observe closely, we find that both nature and human creation are based on a few repetitive fundamental forms, such as:

- Circles — the sun, moon, planets, tree trunks, eyes, wheels

- Lines — mountain peaks, tree branches, building structures

- Triangles — mountain peaks, leaf edges, tents, rooftops

- Lattice patterns — spider webs, honeycombs, river paths

These geometric forms reflect the natural order of the universe. This is why when humans create something — whether architectural designs, maps, or artworks — they unintentionally repeat these fundamental forms, as nature itself is based on them.

Fractal geometry further demonstrates that certain patterns in nature repeat infinitely across scales.

Many philosophers and mystics have supported this idea:

- Plato believed that every material thing is a copy of perfect, ideal forms, known as Platonic forms. Circles, triangles, and squares are not merely mathematical symbols but cosmic principles. Every object reflects these “pure forms.”

- Plato wrote: “Beauty and order are hidden within the original structure of nature.”

- Pythagoras asserted that the universe is built on numbers and proportions, with harmony and ratios forming the foundation of all shapes and phenomena — a concept that led to sacred geometry.

- In the 16th century, astronomer Johannes Kepler observed that planetary orbits follow precise geometric ratios, writing that “God created the world according to geometry”.

- In modern times, Benoît Mandelbrot demonstrated that natural phenomena — trees, clouds, mountains, rivers — all exhibit repeating patterns, known as fractal geometry, a scientific extension of these philosophical ideas.

Similarly, Sufi philosophy speaks of a “pattern of nature” or “primordial design”, where every particle in the universe reflects an original archetype. From this insight emerged the famous Sufi proclamation of Manṣūr al-Ḥāj , “Anā al-Ḥaqq” (I am Truth/God) and the doctrine of Waḥdat al-Wujūd (Unity of Being).

The mandala, primarily associated with Sanatan Dharma and Buddhism, also embodies this concept, symbolizing spirituality, meditation, and cosmic harmony. In Hindu Vedanta, the mandala represents the cosmic order. The word “mandala” comes from Sanskrit, meaning “circle” or “a system revolving around a center.” In Buddhism, mandalas are tools for meditation and spiritual development. Tibetan sand mandalas are especially famous, symbolizing impermanence and Nirvana, and represent the abodes of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

In Balochi, a similar word “Mangal” refers to a circle, and bracelets are called “Manglik”, reflecting the circular symbol of the universe, the spirit, balance, and the continuity of life. Historically, mandalas in ancient India were tied to yogic, tantric, and meditative practices, serving as spiritual maps of the cosmos. Over time, the mandala evolved into a global art form, symbolizing spiritual balance, mental calm, and self-awareness.

A mandala is not a single, fixed shape; it is a spiritual and artistic pattern that generally radiates outward from a center using circles, geometric forms, and symbols. It begins with a point or circle, considered the center of the spirit or universe, around which circles, squares, triangles, flower petals, or geometric patterns expand. Each layer represents a spiritual or psychological dimension. Mandalas are always symmetrical, reflecting the cosmic order and spiritual balance.

Therefore, there is a clear difference between the Baloch martyrs’ symbol and a mandala. A mandala is not defined by a specific shape; merely using circles does not make something a mandala, although domes, mihrabs, and mosaic tilework in mosques may resemble mandala-like radial patterns.

This raises a question: how can we claim that any particular symbol, idea, or material form belongs exclusively to us? Even Baloch embroidery shows striking similarities with patterns found in Ukraine and other parts of the world.

Yes, the Baloch nation is not extraterrestrial; it shares common heritage with others on this earth.

I believe we exist on this eternal circle as a small point — yet neither the circle can exist without us, nor can we exist without the circle.

Explanation of the Baloch Martyrs’ Symbol :

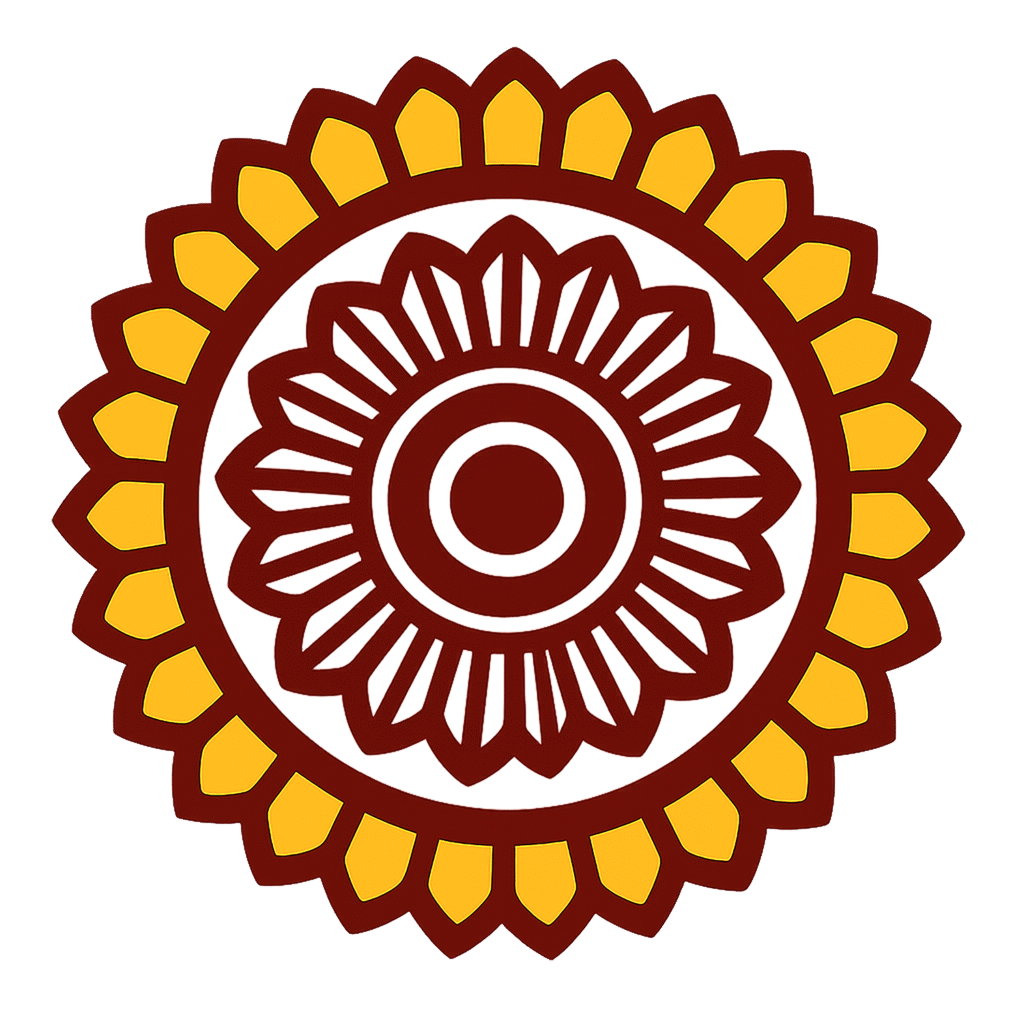

The symbol consists of two concentric shapes , each carrying deep symbolic meaning:

- Inner Layer:

An open flower with 17 petals — a symbol of life, spirit, and renewal (rebirth) , reflecting the beauty of the martyrs’ character and the nation’s respect for them.

◦ The flower consists of three layers or waves.

- Center: A deep maroon point, representing our national unity . Despite differences in language, lineage, and regional divisions, the Baloch are one nation.

- Maroon circle around the center: Emphasizes that the survival of the nation depends on preserving and protecting its unity.

- Flower petals:Represent the greatness, beauty, and national respect of the martyrs’ character, serving as a tribute from the nation.

- Number 17: Symbolizes spiritual balance, faith, and renewal.

◦ It is considered a sign of good fortune in understanding the world, and within this symbol, the martyrdom of the martyrs is honored as a fortunate sacrifice. - The entire central motif is presented in deep maroon, representing the eternal bond between the martyrs’ blood, their sacrifice, and the homeland.

Outer Layer :

A shape resembling a shining sun.

- 28 rays of the sun: Symbolize life, continuity, and the light of sacrifice.

◦ The number 28 is a complete number, connected to the lunar cycle (28 days of the moon) and the passage of time.

◦ It signifies that:

▪Light always comes after darkness.

▪ The continuity of struggle and sacrifice never ends.

▪ Every sunbeam represents the light emanating from a martyr’s sacrifice. - In essence:

◦ “The sacrifices of Baloch martyrs spread across the horizon like the eternal light of the sun’s rays.” - In numerology, 28 represents individuals with balanced personalities, responsibility, and social inclination.

◦ Dividing 28 into four equal parts gives 7 in each, symbolizing the **martyrs’ sacrifices for justice and fairness, expressing that all martyrs deserve equal respect. - The symbol is circular, representing sacrifice and continuous struggle for truth.

◦ Just as a circle has no end, the struggle for justice and its defense continues across generations. Colors - Outer layer (sun rays):Golden yellow →

#F6BD17 - Lines, inner layer, and center flower: Deep red →

#640B0A